For thousands of years Vedic masters have taught that we are seamlessly connected to everything that surrounds us. Although our discriminating mind promotes the sense of separation, our environment – the oceans, rivers, forests, and animals – is an extension of us. In every moment, we transform the energy and information of food, water, and air into the building blocks of our body, while simultaneously exchanging the energy and information of our body with the body of the universe.

Human beings are multidimensional and complex, and yoga reminds us that we live life simultaneously on many levels. In fact, the essential purpose of yoga is the integration of all the layers of life – environmental, physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual. At its core yoga means union, the union of body, mind and soul, the union of the ego and the spirit, the union of the mundane and the divine.

Throughout the centuries great yoga teachers have awakened their contemporaries to the fascinating paradox that although to the mind and senses the world is an ever-changing experience, from the perspective of spirit, the infinite diversity of forms and phenomena are simply disguises of an underlying non-changing reality.

The generally recognized founder of yoga philosophy is the legendary sage, Maharishi Patanjali, whose life is shrouded in the mists of myth and history. According to one story, his mother, Gonnika, was praying for a child to Lord Vishnu, the god who maintains the universe. Vishnu was so moved by her purity and devotion that he asked his beloved cosmic serpent, Ananta, to prepare for human incarnation. A tiny speck of Ananta’s celestial body fell into Gonnika’s upturned palms. She nurtured this cosmic seed with her love until it developed into a baby boy. She named her child Patanjali from the words, pat meaning “descended from heaven,” and anjali, the word for her praying posture. This being, whose life historians date back two centuries before the birth of Christ, elaborated the principles of yoga for the benefit of humanity.

In his classical work, the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali sets the goal of yoga as nothing short of total freedom from suffering. To fulfill this worthy intention, Patanjali elaborated the eight branches of yoga. Each of these components of yoga helps us shift our internal reference point from constricted to expanded consciousness. As we move from local to non-local awareness, our internal reference point spontaneously transforms from ego to spirit, which enables us to see the bigger picture when facing any challenge.

According to Patanjali, whenever we are solely identified with our ego, we bind ourselves to things that do not have permanent reality. This may be attachment to a relationship, a job, or a material possession. It may be attachment to abelief or an idea of the way things should be. Whatever the object of attachment is, the binding of our identity to something that resides in the world of forms and phenomena is the seed cause of distress, unhappiness, and illness.

Remembering that our true self is not trapped into the volume of a body for the span of a lifetime is the key to genuine freedom and joy. Yoga is designed to give us a glimpse of our essential self, by taking us from deep silence into dynamic action and back again to profound stillness.

The eight limbs of Yoga

Our body is a field of molecules. Our mind is a field of thoughts. Underlying and giving rise to our body and our mind is afield of consciousness – the domain of spirit. To know ourselves as an unbounded spirit disguised as a body/mind frees us to live with confidence and compassion, with love and enthusiasm.

To remove the veils that hide the deepest layers of our being, in the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali elaborated the eight branches of yoga, sometimes referred to as the eight limbs (ashtanga). The ashtanga aren’t necessarily sequential stages. Rather, they serve as different entry points into an expanded sense of self, through interpretations, choices, and experiences that remind you of your essential nature. These are the components of Raja Yoga, the royal path to union.

2. Niyama: The internal dialogue of conscious beings

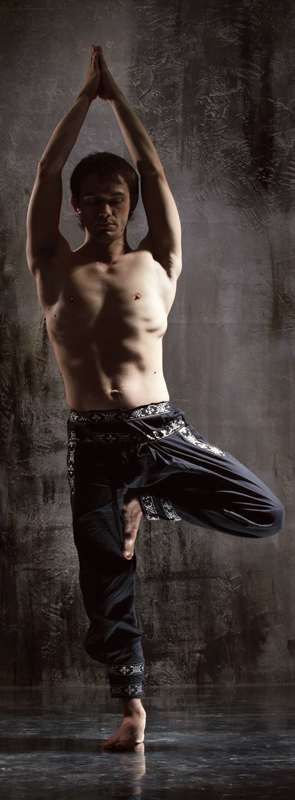

3. Asana: The intimate relationship between our personal and extended bodies

4. Pranayama: Awareness and integration of the rhythms, seasons, and cycles of our life

5. Pratyahara: Tuning into our subtle sensory experiences

6. Dharana: Evolutionary expression of attention and intention

7. Dhyana: Resonating at the junction point between the personal and the universal

8. Samadhi: The progressive expansion of the self

The first branch of Yoga: Yama

In classical yoga, there are five yamas, a Sanskrit term that is commonly translated as the appropriate codes of behavior. We can describe the yamas as the spontaneously evolutionary behavior of an enlightened being. In working with the yamas, however, we must be alert to avoiding the tendency to use them to judge ourselves and other people. There is agreat potential for getting trapped in ideas of right and wrong, better and worse, good and bad. A kind of heavy morality can creep in, and with that comes a certain kind of arrogance of judgment that ends up constricting our hearts and minds rather than expanding them.

We believe that it is more helpful to see the yamas as how conscious beings behave in the world, how they treat other people, and how they treat themselves. They are about how we can make the most efficient use of our energy and live in a state of spontaneous openness to the progressive unfolding of this connectedness between our individuality and our universality. With this perspective in mind, let’s look at each of the five yamas:

1) Ahimsa

While traditionally translated as “nonviolence,” we believe that ahimsa is really about how a person can travel through the world, through the realm of form and phenomena, in a way that does no harm…where every thought and every action and every word in some way or another is nourishing to the ecosystem. Ahimsa is that state where we’re naturally flowing through life without creating unnecessary perturbations.

In daily life, ahimsa is about choosing actions that create the greatest level of harmony between our personal body and the extended body of the universe. When faced with a choice, we can ask ourselves, “In this situation, which possibility offers the maximum evolutionary value? Which choice is the greatest expression of my values, nonviolence, self-referral, and abundance?”

2) Satya

The second yama is truthfulness or satya. It is an expression of being in a state of such complete present-moment awareness that judgment doesn’t need to enter in. In this expanded state, we are able to observe without evaluating. We accept the world as it is, recognizing that reality is a selective act of attention and interpretation. Recognizing that truth is different for different people and in different states of consciousness, we commit to life-affirming choices that are aligned with an expanded view of self.

Patanjali described truth as the integrity of thought, word, and action. We speak the sweet truth and are inherently honest because truthfulness is an expression of our commitment to a spiritual life. The short-term benefits of distorting the truth are outweighed by the discomfort that arises from betraying our integrity. Ultimately we recognize that truth, love, and the divine are different expressions of the same undifferentiated reality.

3) Brahmacharya

The third yama, brahmacharya, is often translated as celibacy or as the control of sexual energy. We believe this is alimited view of this yama. Brahmacharya derives from the word brahman, meaning “unity consciousness,” and achara, meaning “pathway.” In Vedic society, people traditionally chose one of two paths to enlightenment – the path of the householder or the path of a renunciate. For those choosing the path of a monk or nun, the path to unity consciousness naturally includes forsaking sexual activity. For the vast majority of people choosing the householder path, brahmacharya means rejoicing in the healthy, balanced, and responsible expression of creative energy.

The essential creative power of the universe is sexual, and we are each a loving manifestation of that energy. Seeing the entire creation as an expression of the divine impulse to generate, we can celebrate the creative forces. Brahmacharya means aligning with the creative energy of the cosmos. It is about using our life energy impeccably, not wasting a single precious drop.

4) Asteya

The fourth yama, asteya or honesty, means to be fully established in a state of self-referral, in which we relinquish the idea that things outside ourselves will provide us with security and happiness. Lack of honesty almost always derives from fear of loss – the loss of money, love, position, or power.

The ability to live an honest life is based upon a deep connection to spirit. When inner fullness predominates, we lose the need to manipulate, obscure or deceive. We stop trying to please people, because pleasing is always based on a sense of inadequacy. Honesty is the intrinsic state of a person living a life of integrity. According to yoga, life-supporting, evolutionary behaviors are the natural consequence of expanded awareness.

5) Aparigraha

The fifth yama, aparigraha, is generosity or a state of ever present abundance. As we shift from identifying with our limited ego self into an expanded awareness of our essential spiritual nature, we spontaneously express generosity in every thought, word, and action.

Aparigraha implies the absence of aversion. Established in aparigraha, our attachment to the accumulation of material possessions loses its hold on us. It does not mean that we don’t enjoy the world; we are simply not imprisoned by it. The practice of yoga, which cultivates expanded awareness, awakens generosity because nature is generous.

The second branch of Yoga: Niyama

Niyama can be defined simply as the internal dialogue of enlightened beings. Whereas the yamas are about how conscious beings behave, the niyamas are about how they think. As with the yamas, it’s important not to get trapped into arigid sense of morality, thinking that there is a right or wrong way to think.

To a great degree, the niyamas are about cultivating self-acceptance. From an early age, most of us received messages about how we “should” be and most of us have tried so hard to squeeze ourselves (and others) into these molds. When we finally stop trying to be how other people want us to be, we can experience our authentic self, which is perfect exactly as it is…an expression of the divine.

In this expanded state of consciousness, our thoughts and words spontaneously resonate at the highest level of expression. As we progressively allow ourselves to be authentic expressions of the “is,” of the divine presence, then our niyamas naturally come into alignment with the experience of awakened beings.

According to yogic philosophy, there are five main qualities that emerge as a result of living an authentic, balanced life:

-

- Saucha (Purity)

- Santosha (Contentment)

- Tapas (Discipline)

- Swadhyaya (Spiritual Exploration)

- Ishwara Pranidhana (Surrender to the Divine)

Let’s look at each of these qualities in more detail.

1) Saucha

The first niyama is saucha, whose literal translation is “purity.” Focusing on purity adds little value to life if it encourages ajudgmental mind-set, but it is of great value if we see our choices in terms of nourishment versus toxicity. Our body and mind are constructed from the impressions, sensations, experiences, and food that we ingest. Yoga, and the cultivation of saucha, encourages us to consciously choose those things which are nourishing to our body, mind and soul.

2) Santosha

Santosha is usually translated as “contentment” and is best described as the bliss of present-moment awareness. Through the practice of yoga, our experience of the present moment quiets the mental turbulence that disturbs our contentment – contentment that reflects a state of being in which our peace is independent of situations and circumstances happening around us.

When we struggle against the present moment, we struggle against the entire cosmos. Contentment emerges when we relinquish our attachment to the need for control, power, security, and approval.

Keep in mind, however, that contentment doesn’t imply acquiescence or passivity. Yogis are committed in thought, word, and deed to supporting evolutionary change that enhances the well-being of all sentient creatures on this planet. Santosha implies acceptance without resignation.

3) Tapas

The third niyama, tapas, is traditionally translated as discipline or austerity. The word tapas means fire. When the fire of ayogi’s life is burning brightly, he or she is a beacon of light radiating balance and peace to the world. The fire is also responsible for digesting both nourishment and toxicity. A healthy inner fire can metabolize all impurities.

While people often associate discipline with deprivation, it can actually be extremely nourishing. For example, people who have established a yogic lifestyle may rise early, meditate daily, exercise regularly, eat in a healthy, balanced way, and go to bed early because they directly experience the benefits of harmonizing their personal rhythms with those of nature. Tapas is embracing transformation as the pathway to higher consciousness.

4) Swadhyaya

Self-study or swadhyaya is the fourth niyama. Traditionally this is interpreted as being dedicated to the study of spiritual literature, but at its heart, self-study means looking inside. There is a difference between knowledge and knowingness. Yoga advises us not to confuse information with wisdom, and self-study helps us understand the distinction. Swadhyaya encourages self-referral as opposed to object-referral. Our value and security come from a deep connection to spirit, rather than from the things that surround us. When swadhyaya is lively in our awareness, joy arises from within, rather than being dependent upon outer accomplishments or acquisitions.

5) Ishwara Pranidhana

The final niyama, ishwara pranidhana, is often translated as faith or surrendering to the Divine. Ishwara is the personalized aspect of the infinite. Even when considering the boundless, the human mind wants to create boundaries. Ishwara is a name that makes the infinite and unbounded field of intelligence more familiar or approachable. We could just as easily substitute the name God, Allah, Jehovah, Source, Universe, or any of the other names for the Divine. Ultimately, ishwara pranidhana is surrendering to the wisdom of uncertainty. When we relinquish our attachment to the past and embrace the unknown, we are established in present moment awareness – the only place where transformation, healing, and creativity can unfold.

The third branch of Yoga: Asana

Asanas are usually defined as the various yogic postures designed to bring balance and harmony to the physical body, particularly the musculo-skeletal system. Asana is part of the Ayurvedic treatment system for the physical body. Postures can be used to increase vitality or to balance the doshas. They can be adjusted to target certain organs or weak spots in the body.

At a deeper level, asana refers to the complete expression of mind-body integration, a state in which we become conscious of the flow of prana resonating in every molecule of our body and in every thought and every experience.

The essence of asana isn’t about straining to get our body into a particular posture; it’s about surrender, opening, expanding, and enhancing our flexibility, balance, and strength. The practice of asanas is a way to expand our own sense of self and experience the joy of being incarnated in this physical body. At the same time, it allows us to create an intimate dance between our individuality and universality and celebrate the essence of this connection.

The fourth branch of Yoga: Pranayama

Prana is the life force that flows throughout nature and the universe. When prana is flowing freely throughout our body/mind we will feel healthy and vibrant. When prana is blocked, fatigue and disease soon follow. The concept of an animating force is present in every major wisdom and healing tradition. It is known as chi or qi in Traditional Chinese Medicine, ruach in the Kabalistic tradition and ki in Japanese martial arts. The essence of prana is that deep connection between our rhythms, seasons, and our cycles of our life.

According to Patanjali, a key way to enliven prana is through conscious breathing techniques known as pranayama. There is an intimate relationship between our breath and our mind. When our mind is centered and quiet, so is our breath. When our mind is turbulent, our breathing becomes distorted. Just as our breath is affected by our mental activity, our mind can be influenced by the conscious regulation of our breathing. There are a number of classical pranayama breathing exercises designed to cleanse, balance, and invigorate the body.

When we are tuned into the pranic energy in our body, we spontaneously become more attuned to the relationship between our individuality and our universality. In this way, pranayama can take our awareness from constricted to expanded states of awareness.

The fifth branch of Yoga: Pratyahara

The fifth branch of yoga is known as pratyahara – a word that is traditionally translated as “control of the senses” or “sensory fasting.” In our view, the essence of pratyahara is temporarily withdrawing from the world of intense, externally imposed stimulation so that we can tune into our subtle sensory experiences.

Yoga and Ayurveda recommend that we take time to disengage from the exterior world so that we can hear our inner voice more clearly. Meditation is a form of pratyahara since, in the space of restful awareness we disengage from the outside environment. When the mind’s attention is withdrawn from the sensory field, the senses naturally come to rest.

In a way, pratyahara can be seen as sensory fasting. The word pratyahara is comprised of the root prati meaning “away,” and ahara meaning “food.” If we fast for a period of time, the next meal we eat will usually be exceptionally delicious. Yogasuggests that the same concept applies to all our experiences in the world. If we take the time to withdraw from the world for a little while, we will find that our experiences are more vibrant.

Pratyahara also means paying attention to the sensory impulses we encounter throughout the day, limiting to the greatest extent possible those that are toxic, and maximizing those that are nourishing to our body, mind and soul. It’s about being aware of and doing our best to avoid situations, circumstances, and people who deplete our vitality and enthusiasm for life.

The sixth branch of Yoga: Dharana

Dharana is mastery of attention and intention. As the ancient sages taught, whatever we put our attention on grows stronger in our life, so it is important to be intimately aware of where we are focusing our thoughts and energy.

By learning to value our attention as a precious commodity, we will be able to consciously create well-being and success in our life. Whether our goal is building a business, becoming physically fit, improving a relationship, or developing aspiritual practice, the object of our attention is enlivened by our awareness.

Once we activate something with our attention, our intentions have a powerful influence on what things manifest in our lives. According to yoga, our intentions have infinite organizing power. Our intention may be to heal an illness, create more love in our life, or become more aware of our own divinity. Simply by becoming clear about our intentions, we will begin to see them actualize in our lives. When our awareness is established in being and we have a clear intention, the universe’s infinite organizing power will manifest our desired outcome with effortless ease.

Dharana techniques involve various means of directing our attention, such as focusing on particular objects or ideas, meditation, and the energy of the chakras. Another method is focusing the mind on the inner space that dwells within the heart. There are innumerable ways to practice this sixth branch of yoga.

The seventh branch of Yoga: Dhyana

Dhyana in its essence is about vibrating between the level of the personal and universal, between mind and no-mind, between constriction and expansion. Even in constriction, we are not attached to a particular outcome or resisting what is; we are just observing with witnessing awareness. In the process, we become increasingly awake and aware of the connection between mind and no-mind, without judging either state. In accepting that we are both an expression of the divine and a skin-encapsulated ego, life becomes lighthearted and fun.

Meditation is one of the most direct ways to develop this state of ever-present witnessing awareness. We may also meditate on an internal object that we visualize, or an idea such as truth or oneness. The object of our meditation may be without form altogether and totally open, as with Primordial Sound Meditation. All meditation consists of dwelling in witnessing consciousness and observing what we see, rather than projecting an involvement with it. This frees our consciousness from outer attachments in which there is pain and distortion.

The eighth branch of Yoga: Samadhi

Yoga defines samadhi as being established in pure, unbounded awareness. Going beyond time and space, beyond past and future, beyond individuality, samadhi is an experience of the underlying divine nature in all things and in ourselves.

Immersing ourselves in samadhi on a regular basis allows our internal reference point to shift from ego to spirit. We experience ourselves as part of the infinite field of unbounded consciousness. By regularly engaging in that state, we are able to live and perform our actions in the world as an individual even as we rest in the awareness of our universal nature.

The integral practice of Yoga

All eight limbs are integral to the practice of yoga and each serves to give proficiency in the others.

-

- The first five limbs of yoga – yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, and pratyahara – are said to be “outer aids.” They harmonize the outer aspects of our nature, body, breath and senses, to allow the inner or meditative process of yoga to proceed.

- The last three limbs – dharana, dhyana, and samadhi – are said to be “inner aids.” They are the methods by which we can recognize the projections of consciousness and the subtle levels of the mind.

The ancient sages taught that all life is yoga; that is, all life is aiming consciously or unconsciously at reintegration and unification of its forces with the cosmic life. The essential purpose of yoga is the integration of all the layers of life – environmental, physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual.

David Simon, M.D., is a world-renowned authority in the field of mind-body medicine, a best-selling author, and the co-founder of the Chopra Center for Wellbeing in Carlsbad, California. The Center offers programs and retreats focusing on mind-body health, Ayurveda, meditation, yoga, and other practices for physical health, emotional wellbeing, and spiritual awakening. www.chopra.com

David Simon, M.D., is a world-renowned authority in the field of mind-body medicine, a best-selling author, and the co-founder of the Chopra Center for Wellbeing in Carlsbad, California. The Center offers programs and retreats focusing on mind-body health, Ayurveda, meditation, yoga, and other practices for physical health, emotional wellbeing, and spiritual awakening. www.chopra.com