Patience at Work

Many disagreements do not really go very deep. They are not settled by arguing. They are not solved through analysis and synthesis. They are resolved – or dissolved – through patience. Without patience, you start retaliating, and the other person gets more upset and retaliates too. Soon you have two people out of control. Instead, listen to what the other person is saying. How can you even answer if you do not listen? Refrain from answering immediately, and when you can, try a smile or a kind word; it can do so much to relax the atmosphere. Little by little, you can try a kind phrase, then a kind sentence. When you become really expert in love, you can throw in a kind subordinate clause.

This actually quiets the other person. Kind language is a sedative. When you answer harsh words or disrespect with kind words, you are writing a prescription and passing it to the other person: “Take this. It will keep your blood pressure down and calm your mind.”

This is a vital skill, for whatever our role in life – student, teacher, doctor, parent, carpenter – we can’t depend on people doing what we say in just the way we like. If you are a doctor, for example, you cannot expect to get patients who are well behaved, courteous, and prepared to carry out instructions cheerfully. You are going to get many whiny children and irritable adults. You will see people who are short-tempered, ask embarrassing questions, demand to see your diploma, and wouldn’t dream of following instructions they do not like. This is part of being a doctor. And every encounter is a lesson in love. When the nurse comes in and says, “You’ve got a real pill this time, doctor,” you can say, “Terrific! I’m getting a lot of lessons today.” Maybe the patient hasn’t slept. He has been in pain for forty-eight hours, hasn’t been able to eat his breakfast; do you expect him to be an angel? If you can be sympathetic, it may help as much as any medication. It is not only drugs or surgical procedures that help the sick. It’s also the faith that you are not just doing a job for pay or for some personal research interest; you are concerned about his welfare.

An End to Loneliness

“Once you realize the Self, the divine core hidden in your own consciousness,” the Upanishads say, “you will never be lonely again.” Loneliness is epidemic today; even people with money and lofty social status can be stricken by this virus. Once we realize the Self, we don’t have to beg, “Josie, please love me. Bernard, please be my friend.” When the lotus blooms, Sri Ramakrishna reminds us, it has no need to say, “Bees, come to me”; they are already looking for blossoms. Similarly, when you discover the Self, you will find that you draw people to you naturally for inspiration, consolation, and strength.

By the same token, we can move closer to the Self by moving closer to other people. This is not always easy, especially at those times when we feel inclined to hole up inside ourselves. It is sometimes difficult, even exasperating, to work with others with different methods and ideas. As we learn to give and take and to pay more attention to the needs of others, however, security comes without our seeking it; we no longer feel isolated in a meaningless world.

When we live harmoniously with others, we do help them, but it is we who grow spiritually. When we avoid opportunities to work and live with others, we lose this precious opportunity for growth, which can come to us in no other way.

A Perfect Day

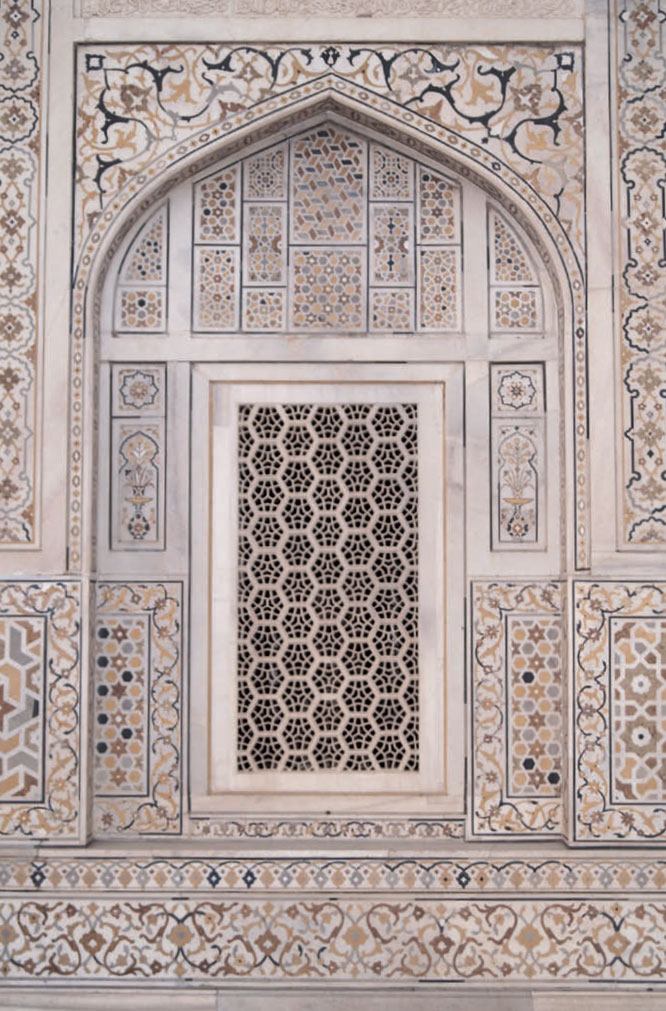

Mogul art, one of the highlights of artistic achievement in India, is often in miniature. The artist concentrated on very small areas, working with such tenderness and precision that one has to look carefully to see the love and labor that has gone into the image. Living is like Mogul art: the canvas is so small and the skill required so great that it’s easy to overlook the potentialities for artistry and love.

One beautiful, balmy Sunday soon after my mother and nieces arrived from India, Christine and I took them out for ice cream. I rode in the back, with Meera on one side and Geetha on the other. They chatted gaily the whole way, without a break, asking me all kinds of questions. I kept reminding myself of what most of us older people forget: that every child has a point of view. They have their own way of looking at life, which makes them ask these questions, and for them things like why Texaco and Mexico should be spelled differently when the endings rhyme are matters of vital importance.

When we got to town, we had to walk slowly because my mother was almost eighty. The children, however, wanted to run – and they wanted me to join them. I didn’t say, “It’s not proper for a pompous professor to be running about. It takes away from his pomp.” Instead, I made a good dash for it. I thought I would meet with appreciation, but little Geetha just objected, “You’re not supposed to step on the lines.” There was no “Thank you,” no “Well done”; I had to do it all again.

Geetha was just learning to read, so when we reached the ice cream parlor she stood staring at the big board, examining each item. In India we usually have only two or three choices, so she was really baffled. “Uncle,” she said, “What are all these flavors?”

She tried to read a few and then asked, “What is that long word I can’t read?”

I said, “Pistachio.”

“That’s my flavor.” So she got that, double dip, and Meera got Butter Brickle.

They nursed their cones all the way home. I was in the back seat between them again, and every now and then they would exchange licks – across my lap. My first impulse was to warn, “Don’t drip on me!” Then I reminded myself that from their point of view ice cream is much more important than clothes. We made it home without incident, with the girls and my mother laughing happily about a perfect day.

We learn patience by practicing it, the Buddha says. What better way than by sharing time with children at their own pace and seeing life through their eyes?

A Garland of Wildflowers

Krishna is often portrayed as a young man with a garland of wildflowers, the delicate blooms of the forest, around his neck. It’s not a sophisticated corsage from the florist’s shop; everything is natural, simple, beautiful.

The beauty and compelling attraction of this image is universal. Krishna is the spark of divinity in every heart, constantly calling us to return to him. As long as we are alienated from our real Self, we will be restless and unfulfilled, for this divine spark is our deepest nature, the innermost core of our being.

Indian poets have always been fond of the imagery of flowers. Meera, one of the most beloved saints of medieval India, tells Krishna in a song, “I am going to wear you like a flower in my hair, like earrings in my ears, like a garland around my neck, so that I remember you always.” If we remember who is the source of all beauty, all plants will remind us of the Lord.

Houseplants are everywhere today; people have African violets on their desks at work, ferns on the TV, fig trees in the corner of the living room. In some places, it is fashionable to tear down a wall or open up a window and attach a miniature greenhouse. Why not do the same with patience and forgiveness? We can surround ourselves with compassion, open up our lives to goodwill. All these flourish with just a little care. When you fly off to Iceland on a tour, don’t you ask your neighbor to take care of your African violets – spray them, chat with them, pick off the bugs? With the same attention, houseplants like love and tenderness will blossom in your life year-round.

Sri Krishna’s garland of wildflowers is always fresh from the forest. When you or I receive flowers on a special occasion, we have difficulty keeping them fresh, but Krishna’s garland never seems to fade. The Hindu scriptures say that this is a sure giveaway of a divine being. If you ever meet anyone whose corsage or buttonhole bloom never wilts, be alerted: this is no ordinary Joe or Jane!

Peaceful Sleep

My mother must have been born kind; in seventy years I don’t remember her uttering a hurtful word to anyone. But I was like everyone else. As children do, I sometimes said hurtful things that I was ashamed of afterward, and when I did, it would torment me. I would toss and turn throughout the night, and the next morning I would go straight to my cousin or whoever it was and say, “I hope what I said yesterday didn’t hurt you.” To make it worse, he would look at me blankly and ask, “What was it?”

I used to complain to my grandmother, “This isn’t fair! He is the one who should feel hurt, and he doesn’t even remember it. Why should I be the one who can’t sleep?”

“That is the makings of what is in store for you,” she would say mysteriously. “That is the way you learn.” I didn’t understand, and I could never get her to explain.

But she was right: my motivation grew. If somebody said something rude to me, I learned to hold back a rude response and think, “Oh, no. I don’t want to lie awake at night!” That is how it began. Today that reversal has gone so far that if someone says or does something unkind to me I feel sorry for that person, not for myself.

Be Kind – But Use Discrimination

My grandmother was fond of a proverb: “Lack of discrimination is the source of the greatest danger.” The capacity to know what should be done and what should not be done is called “discrimination,” and it is one of life’s most precious secrets.

In life, we will meet people with whom we have to be careful, using our discrimination. There are many situations in which we must proceed with caution.

In our Indian tradition we have countless stories to illustrate this, usually with a touch of homely humor. In one story, two boys, a bigger boy and a smaller boy, go to a sweetmeat shop to get two treats called laddus, which are very popular with children. They are extra large laddus, so the bigger boy is carrying them. Suddenly, one treat falls and rolls into the gutter. The bigger boy tells the little fellow, “There goes your laddu!”

So the moral of the story is to be careful with such people. The little fellow should have sized up the situation and said, “I’ll carry mine.”

Another story is about a practical, down-to-earth spiritual teacher who has a young, tenderhearted disciple. After telling the disciple that everybody has a divine core, the teacher wants to see whether the young man has understood correctly. He sets him a simple test, telling the boy he wants a bucket from the bazaar.

Later that day, when the teacher brings hot water in the bucket for his bath, most of it just disappears. He calls to the boy, “Did you bring this bucket?”

“Yes.”

“Where did you get it?”

“From one of the divinities in the bazaar.”

“Oh, you got it from one of the gods in the bazaar?” the teacher asks with a smile. “Did you fill it with water?”

“No, I just trusted him.”

The teacher says kindly, “You should have tested the bucket.”

Similarly, if we go to the supermarket, there are certain things we must do. Always read the labels. Always check the price. Everywhere, a certain amount of care should be taken, a certain amount of responsibility should be assumed.

Exercising discrimination is part of being kind. We need to combine a soft heart with a hard nose.

“Be Kind, Be Kind, Be Kind”

The great medieval mystic Johan Ruysbroeck, when asked how to become perfect, gave the simple answer: “Be kind, be kind, be kind.” When we remove all unkindness from our deeds, words, thoughts, and feelings, what remains is our natural state of love.

This may sound simple, but it demands many years of sustained effort to eliminate all unkindness from our inner and outer lives. Some would say that this is humanly impossible – that it is beyond human nature to return kindness for unkindness even in our thoughts. Only when we see someone who has attained these heights do we begin to say, “Maybe it is possible, after all.” When we come in contact with such a person, we know there is no limit to our human capacity to love.

Eknath Easwaran (1910–1999) is known and respected around the world as a teacher and author of books on yoga, passage meditation, and spirituality. He came to the U.S. in 1959 as a Fulbright scholar and founded the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation in 1961. His work is carried forward through publications and programs offered in Tomales, California, and other locations around the U.S. www.easwaran.org

Eknath Easwaran (1910–1999) is known and respected around the world as a teacher and author of books on yoga, passage meditation, and spirituality. He came to the U.S. in 1959 as a Fulbright scholar and founded the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation in 1961. His work is carried forward through publications and programs offered in Tomales, California, and other locations around the U.S. www.easwaran.org