The energy we need is always present; we just need to learn to release and harness it. When I talk about a slower pace of life, I don’t mean an idle sail far from any stirring breeze, with no adventure beckoning us. If anything is less desirable than a speeded-up life, it is a life of boredom and indifference. When we slow down and train attention at the same time, we are naturally cultivating enthusiasm for every day. We begin to face each task with energy and focus. This is a difficult balance to achieve – not hectic, not blasé – but it is a quality to be cultivated if we want to live at our best.

I found a good illustration of the challenge and rewards of this kind of balance when I went with friends to a favorite restaurant overlooking San Francisco Bay. We arrived early for lunch, so even though the place is very popular, we got a good table near the window. Soon I was completely absorbed in the scene. Outside the sun was bright and the wind was high. Hundreds of seagulls were tossing about in the sky, and as many sailboats on the waves.

I couldn’t help admiring the skill of some of the sailors. While we watched, one boat was racing toward us over the water with its sail almost dipping into the sea. My heart leapt into my mouth and I wanted to cry, “They’re gone!” But the agile crew kept leaning out over the water on the opposite side, and the boat never quite turned over.

Others on the water were not so skillful. They would catch a strong wind in their sails and pick up impressive speed, but I would see their boats suddenly careen erratically as if they had a life of their own. I could sympathize. How like life in today’s restless, unpredictable world, where we often feel we are running before the wind in a stormy sea.

Below the restaurant window scores of other boats were tied up, hugging the shore, their lines slapping idly in the breeze. On their decks, men and women in summer clothes were enjoying drinks, chatting, or reclining in lounge chairs in the sun, perhaps dreaming that they, too, were sailors while their boats remained tied up comfortably at the dock.

Most of us have seasons like these sailors. At times we surge with energy, so much so that our lives are almost out of control. At other times we face blocks, can’t seem to get on top of things, can’t seem to move. Often these phases are accompanied by mood swings between high and low, ebbs and flows of self-esteem.

And, of course, there are times when we maneuver gracefully through events which at other times would have hopelessly becalmed or capsized us, navigating unerringly towards our goal. That is life.

According to yoga philosophy, the human personality is a constant interplay of these three elements – inertia, energy, and harmony. All three are always present, but one tends to be dominant at any given time – in a day, throughout a stage of life, over a life itself. And they lie on a continuum of energy. Just as matter can exist as a solid, a liquid, or a gas – ice, water, or steam – our own energy-states move in and out of inertia, activity, and harmony.

Inertia, of course, is least desirable. Energetic activity is much more desirable, but without control it only consumes our time and gets us into trouble. Harmony is the state we desire to live in. Fortunately, because all three are states of the same energy, each of these states can be changed into another. Just as ice can be thawed into water and water turned into steam, inertia and activity are both full of energy which can be converted into a state of dynamic balance full of vitality and power.

Spotlight

It is wonderful to have abundant energy, for then no obstacle is too big to overcome. But there can be danger when a person has more energy than he or she knows what to do with. If we lack direction and an overriding goal, we are likely to misunderstand the signals that life sends us. Life is saying, “Come on! Venture out on the high seas, brave the adventures I send, and perfect the skills you need to fulfill your destiny.” But we don’t hear this message clearly. Somehow the signal gets garbled, and we can’t tell where the call is coming from.

“It is not enough to be busy,” Thoreau pointed out. “The question is: What are you busy about?” This is a useful question. To know when to plunge into an activity and when to refrain from it requires judgment – detachment and discrimination. In India we have a saying, “Lack of discrimination is the greatest danger.” When we lack discrimination, we do not know when to throw ourselves into something and when not to get entangled in it – and the more energy we have, the more it is going to get us involved in sticky, even dangerous situations from which it is difficult and painful to escape.

I think it is Henri Bergson, the French philosopher, who said that the human species should not be called Homo sapiens, “the creature that thinks,” but Homo faber, “the creature that makes things.” This is an astute observation. Most of us are concerned with making things: houses, roads, helicopters, guitars, pasta, anything. As long as we can make something, we find some satisfaction in living.

Take a walk in any large shopping mall and look in the shop windows. How many places are selling something that is necessary? How many are selling items that are beneficial? We can accommodate a whole mall in two or three shops if we rule out things which have been made just because Homo faber fever has got us.

Energy out of control has two characteristics: burry and worry.

Along the highway I used to see dusty Volkswagen buses with their windows covered with stickers: “Paraguay,” “Turista,” “Mexico.” We can tell the owners are travelers from the stickers they have collected – unless they just bought them in some little shop at the mall. Similarly, if we observe a man or woman who is the victim of overabundant energy, we will see two small identifying stickers: “Hurry” and “Worry.”

Worry goes with hurry because people in a hurry don’t have time to think clearly and make clear decisions, so they are always worried about results. They fret about the conclusions of their research, about the value of their work, about whether they are contributing to the welfare of their students. If you slow down enough to think clearly and act wisely, you have no need to worry because you know you are doing your best.

Energy, to be useful, has to be available when we need it – at our beck and call.

One fascinating thing about people with a lot of energy is that it’s not at their beck and call. When energy is overflowing, it tends to drive them; but at other times it dries up. This is the other pole of our lives: the times when we just can’t get going.

Often people have energy only when it comes to doing things they like. We all know people who have boundless motivation when it comes to doing what they want to do. They get absorbed in details that seem excruciating to us and pass hours without noticing how much time has gone by. But when it comes to activities that don’t interest them, they may actually seem sluggish and even lacking in energy.

Most of us are like this. We have energy for activities that interest us, but when that energy is blocked it flows elsewhere, to something more attractive. We get busy doing those other, more attractive things and can’t find time for what needs doing.

In India we call this “painting the bullock cart wheels.” Just when the harvest is ready to be brought in, the farmer notices that the wheels of his bullock cart are looking rather shabby. Instead of going out into the fields, he takes a day to go into town for paint and then spends a week painting beautiful designs on the cart wheels. When he finally gets around to harvesting the rice, he has to work twelve hours a day just to keep up.

Even people who are usually energetic can have a mental block when a challenge comes to them. Students often grind to a halt on the eve of finals and find it physically impossible to open a book. I have seen students dismantling their motorcycles the night before exams, which calls for a lot more energy and application than the study of Wordsworth’s “Ode to Immortality.” This is a valuable clue: the problem is not lack of energy, but how to control and direct it.

Most of us don’t have to write papers on Wordsworth. But we do have to fill out our tax returns each year, turn in reports at work, write thank-you notes, clean out garages, and perform countless other tasks that we find distasteful. How many of us decide to put such things off while we work on our car or plant the new vegetable garden instead? Cars and gardens do need attention, but tax returns are urgent. In fact, when the calendar says April 14th, anything else is a distraction.

The energetic, restless, aggressive person is often looked upon as an achiever – a valuable asset who accomplishes much. People who are driven by their own energy can be like steamrollers, rolling relentlessly over any obstacle in their way. Yet when they face a task which promises no personal profit or power, the steamroller may become a rolling stone, perhaps even a sitting stone. Then it cannot push away obstacles; the most it can do is roll.

Inertia is frozen power. The energy is there; it just needs to be released.

Just as water can freeze, thaw, and freeze again, our personal energy surges back and forth between activity and inertia. The energy is there, but it is sometimes frozen and sometimes out of control.

Spotlight

Look at what happens with most of us when we start a fitness program. We see some show on TV over the weekend and are filled with enthusiasm; we get expensive shoes and a fashionable outfit and go to bed Sunday night with the alarm set to go off early for a half-hour run before a good, nutritious breakfast. And for a week the schedule works perfectly. We have a keen appetite after the run, enjoy a nourishing breakfast, and feel invigorated for the rest of the day – all week long.

But when Saturday morning dawns and the alarm goes off, we’re tired and sore. And after all, it is Saturday. There’s no clock to punch at work. What does it matter if we have our run a little later? It’s rather boring, and anyhow, rest is important too.

By the time we wake up an hour or two later, the sun is high and we remember we have a number of other things we need to do. There really isn’t much time for a run. It’s almost eleven when we get to breakfast. Since it’s Saturday, we allow ourselves a sweet roll – with three cups of strong coffee to get going.

By afternoon, serious difficulties have set in. Someone has lent us an old paperback on UFOs, and it’s just been lying around. It doesn’t look particularly elevating, but we really should glance at it before we give it back. Remarkably, it proves rather gripping. After a few pages, we settle down on the couch and get into a comfortable reading position on our back. There is a package of cookies on the table, and we take one or two while we read. One or two won’t hurt.

Eventually we realize that our hand is scraping the bottom of the bag. In fact, only one cookie remains. We’re not particularly hungry any more, but we might as well eat it. We go on reading, and soon we have fallen asleep. We wake up just in time for dinner.

All in all, not such a good day for our fitness program. But it is better than the following day, when we can’t seem to rouse ourselves out of bed at all.

We have a phrase for this in India: “a hero at the beginning.” Plenty of energy at the start, but it fizzles out.

Or the energy cycle may start at the other pole. Years ago I saw an entertaining film about one of those rather seedy detectives whom you grow to love. The opening scene is still vivid. When the fellow drags himself out of bed in the morning he has a three-day growth of beard and can’t even open his eyes. His movements are so sluggish that you think he must have been worked over by gangsters or be suffering from a serious hangover, but it turns out he’s just a slow starter. He manages to get to the kitchen for a strong cup of coffee, and then discovers that he ran out a day or two before. Fortunately he hasn’t done the dishes in a while. He finds some old grounds at the sink, pours in some boiling water, and drinks the result with a grimace while he lights a cigarette. We want to ask, “This is the hero? He can’t even get himself dressed!” But then the phone rings, and the transformation begins. There’s a crisis, someone’s been killed, and within minutes this slow starter is a man of action.

Fortunately, there is a state beyond both phases of this cycle – beyond restless activity and sluggish inactivity too. The energy frozen as inertia can be released, and then all our energy brought under control in a dynamic balance that Fortunately, there is a state beyond both phases of this cycle – beyond restless activity and sluggish inactivity too. The energy frozen as inertia can be released, and then all our energy brought under control in a dynamic balance that allows us to give our best and enjoy life to the fullest.

Everyone likes a man or woman who has gusto and enthusiasm, but it is not enough to have an enthusiastic attitude and lapse when it comes to action. We need the energy and will to carry out our good intentions in whatever field of action we choose. Otherwise, even if we are enthusiastic, we won’t be able to follow through; inertia will block our way. If we take to painting, we won’t get beyond buying paints and canvas; if we decide to learn a language, we will get the books and tapes but not find time for Lesson 2.

Having all our energy in a dynamic balance allows us to give our best and enjoy life to the fullest.

Inertia is like driving with your brakes on. A surprising number of people do this; their brakes are set all the time.

We may have gas in the tank and an engine in top condition, but no amount of potential power helps if we drive when the brakes are on. On the other hand, it means there is no irremediable problem. All that is required is to release the brake.

When energy surges, we have the opposite problem: no brakes at all. Then we can’t stop. We have to move, have to act, have to get involved – which means we can get caught in virtually any activity under the sun.

Often – though not always! – what we get caught in is something we enjoy. Once we get caught in it, however, we can’t think about anything else. I have known many people who tell me that they think about their work day and night because they really enjoy what they do. But they can’t turn it off. They can’t keep from taking their work home or working late at the office, and they can’t turn off their minds when it’s time to sleep. When you talk to them, they are not really listening to you but thinking about their work or their hobby. They may not realize it, but what once seemed so pleasant to think about has become a burden.

We need time for pondering life’s deeper questions instead of always making money or making things. We need time simply to be quiet now and then. There is an inner stillness which is healing, which makes us more sensitive and gives us an opportunity to see life whole.

We need time simply to be quiet now and then: time to reflect on what we are doing what we value, how we are spending our lives. To live in balance, we need to drive the way skilled highway patrol officers do: ready to accelerate if necessary, but always ready to brake when the situation starts to get out of control.

Do you remember those dual-control cars in which you learned to drive? Picture the will – your capacity for discriminating judgment – sitting in a dual-control car as the driving instructor, and desire as the student at the wheel. As long as Desire is driving correctly, Will doesn’t need to do a thing. But the moment Desire starts to do something dangerous, Will takes the wheel, touches the brake, and says, “That’s no way to drive.”

Desire retorts, “How do you know what I was going to do?”“By the look in your eye,” Will replies.

When Will is in control, he can tell from the gleam in the eyes of Desire that what is about to happen is not going to be good for your health, your nerves, or your sleep.

Of course, in the early days, Desire is going to thump on the steering wheel and howl and say, “I’ll call the highway patrol!”

But Will just replies patiently, “I am the highway patrol.”

After a while Desire comes to know that Will is his friend. Thereafter, if there is any difference of opinion, instead of looking upon Will as somebody hostile, Desire will say, “Will, this is something I can’t handle.” And Will says, “Leave it to me.”

This is a perfect picture of the state of balance. It is not that you lose your desires, but your will is always in control. Wherever desire is in control and the will lags behind, there is likely to be trouble – emotional distress, psychosomatic and physical ailments, personal entanglements with painful consequences. These are the problems of energy running out of control. But when will and desire are in harmony, you enter into a state of perfect driving – with power steering, power brakes, power everything. This is victorious living.

Living in balance means living in the present, ready for whatever comes.

As a boy, when I discovered Charles Dickens, I was so enthralled by his stories that as I neared the end, I would read only a couple of pages at a time to make the pleasure last. My little niece was like that with chocolate; when she got a bar of chocolate, she would take just one lick and then wrap it up again and put it aside.

This is all right for children, but when our mind treats life like a bar of chocolate, it will be looking for chocolate all the time. It will always be restless, which is the root cause of all our hurry. And, of course, a restless mind can’t ever be at peace – and how can we expect a mind that’s not at peace to find joy anywhere?

When you live in balance, you are in joy always – not joy in the sense that things always take place in the way you want, but because you are never disturbed and have a quiet confidence in yourself that cannot be shaken. It is one of the fallacies in our modern approach to life that we believe we can be happy only when everything takes place exactly as we want. Actually, I would say that it’s a good thing life doesn’t work that way. Sometimes the best things in life are not what we thought we wanted at all, and the unpleasant experiences are what helped us grow. When your life is in balance, you lose the capacity to be disappointed.

When harmony predominates, it means your mind is at peace, so you cannot be disappointed. It also means you become an utter stranger to loneliness. When you are with people, naturally you are at one with them, but the incomprehensible thing is that when you are alone, too, you are at one with the world.

Spotlight

It is important not to confuse slowness with lethargy. In slowing down, attend meticulously to details. Give your very best even to the smallest undertaking.

I enjoy being with people. It is not social enjoyment; it is not even intellectual enjoyment. It’s a kind of enlightened rapture of being one . . . always. In the early days, I used to feel at home only in a small circle that enjoyed the things I enjoyed. Today I relate to everybody. When I go out, I like to sit in a corner somewhere and just watch “me” passing in many disguises.

I can’t tell you the joy of this. I can be in any country on the face of the earth, I can be with any people, and I will always feel deeply, “These are my people.” Then you are a good friend to your friends and a good friend to those who are not so friendly also. When people praise you, you are at peace; when they criticize you, you are still at peace. You are not any better because of the praise and no worse because of the censure.

This kind of peace of mind cannot be disturbed by any external circumstance. With it you live in freedom, which is the real fruit of slowing down.

Ideas and suggestions

It is important not to confuse slowness with lethargy. In slowing down, attend meticulously to details. Give your very best even to the smallest undertaking.

When it is difficult to start a project or task, try to take the first small step towards completion. For example, if you resist writing a thank-you note to your aunt, tell yourself that you will just get out the stationery and a pen. Often, once this small step is taken, the job will be completed quickly.

When you feel driven to act on an impulse, take your time to ask if this is really what is in your best interest. Observe the ebbs and flows of energy in your day. When are you most alert and energetic? What drains your energy? With careful observation you will be able to identify the swings of energy: perhaps too much caffeine or sugar has left you agitated, and then exhausted. When we see these swings more clearly, we can take steps to enrich our performance, patience, and inner peace.

Most of us find we have energy for jobs and activities we enjoy. Try doing with enthusiasm a necessary job that you don’t particularly enjoy. Put the task you dislike first on your list. With training, you can actually begin to juggle these likes and dislikes to release more energy into your life.

If your life seems cluttered, ask yourself if you have got caught in some hobby that may be harmless but time-consuming. Are you spending more time than you’d like on a pet hobby, a cherished collection? Even worthwhile activities can come to dominate our time if we do not consciously ask this question now and then.

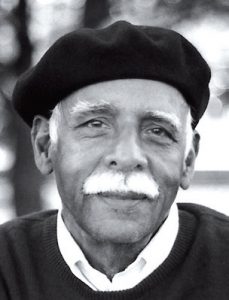

Eknath Easwaran (1910-1999) is respected around the world as the originator of passage meditation and an authentic guide to timeless wisdom. An Indian professor of English literature and a writer and speaker, he came to the U.S. in 1959 and founded the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation in 1961. The centre carries on his work today through publications and retreats. www.bmcm.org

Eknath Easwaran (1910-1999) is respected around the world as the originator of passage meditation and an authentic guide to timeless wisdom. An Indian professor of English literature and a writer and speaker, he came to the U.S. in 1959 and founded the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation in 1961. The centre carries on his work today through publications and retreats. www.bmcm.org